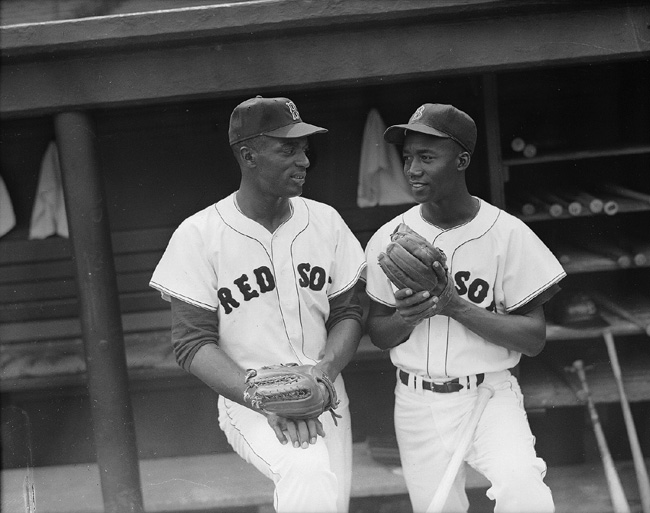

Born in Ponchatoula, La., on Oct. 2, 1934, Mr. Wilson was signed by the Red Sox in 1954 after a sterling season for Bisbee-Douglas of the Arizona-Texas League. He was signed as a catcher and was converted to a pitcher because of his rifle arm.

The subtext of the Red Sox scouting report on Mr. Wilson when he was signed was an indication of the bias in the organization at the time and what Mr. Wilson had to overcome to make it to the major leagues.

It read in part, ''well-mannered colored boy, not too black, pleasant to talk to, well-educated, very good appearance."

''It never bothered me what people said in the stands in Boston," Mr. Wilson told the Globe in 1980. ''What I heard in the South was so much worse. I just wondered why it took me so long [six years] to get there. I was ready long before that."

Despite racial epithets and biased management, Mr. Wilson emerged to become one of the best Sox players on teams that struggled to reach mediocrity.

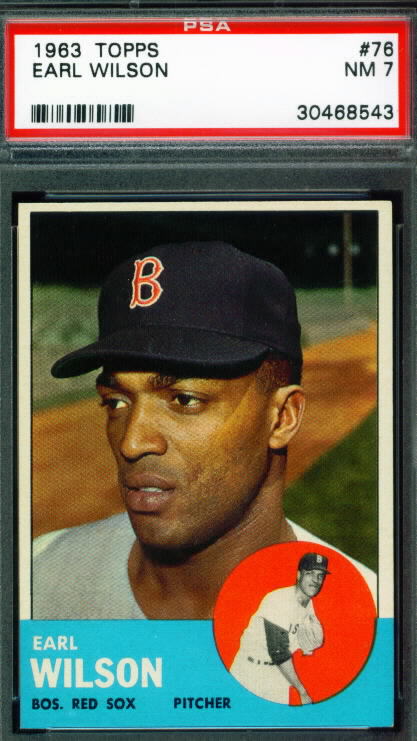

The Red Sox brought up Mr. Wilson to the major leagues on July 29, 1959, just one week after the Sox called up their first African-American ballplayer, outfielder Elijah (Pumpsie) Green. The Red Sox were the last of the original 16 Major League franchises to have an African-American on its roster.

During his seven years with the Red Sox, Mr. Wilson became one of the first professional baseball players to have an agent represent him in contract negotiations.

It all came about because of the no-hitter and a car accident in downtown Boston.

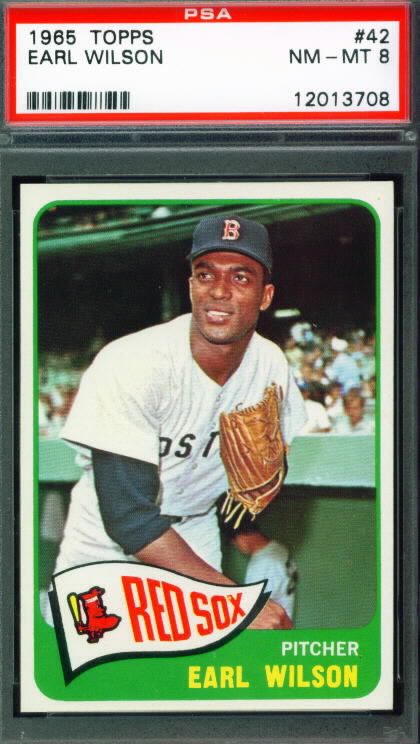

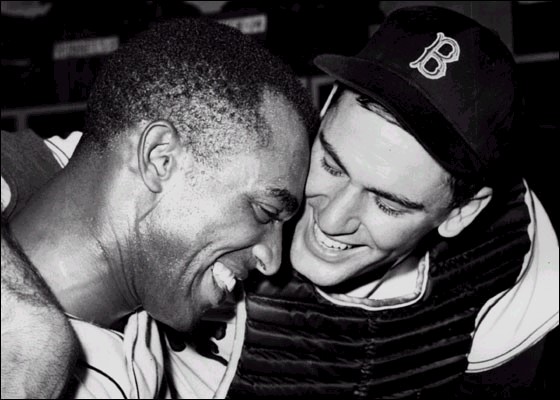

On June 26, 1962, the right-hander not only hurled a 2-0 no-hitter over the Los Angeles Angels at Fenway Park, he provided much of the offense by blasting a home run. After the performance, Sox owner Thomas A. Yawkey tore up his contract and offered a new pact.

At the same time he was renegotiating his contract, Mr. Wilson was involved in a minor accident and was referred to a young criminal attorney, Robert Woolf.

Woolf not only represented him in the accident, but led the contract negotiations and garnered several endorsement deals for Mr. Wilson. For Woolf, it was the start of a career as one of the nation's leading sports agents.

The season of '62 was Mr. Wilson's best with the Sox, finishing with a 12-8 record for a team that finished below .500. In 1966, Mr. Wilson was traded to the Detroit Tigers in a deal for center fielder Don Demeter. Many thought at the time the trade was retribution for outspoken remarks by Mr. Wilson during spring training.

That year, the Red Sox had moved their spring training camp from Scottsdale, Ariz., to Winter Haven, Fla. Mr. Wilson was refused entrance to a nightclub because of his race. Despite requests by the Red Sox to let the matter die, Mr. Wilson refused. He told his plight to sportswriters covering the team, exposing racism and the Red Sox's reaction to it.

''I wasn't going to back down, and the club would rather I'd forgotten about the whole thing," he told the Globe years later.

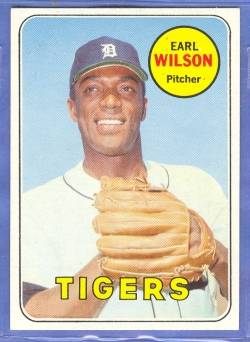

The trade to the Tigers was a blessing for Mr. Wilson. During his years with the Red Sox, they never had a winning record.

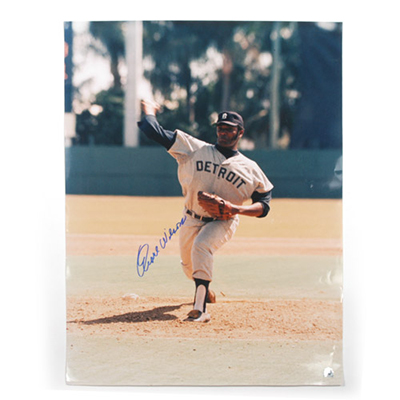

Mr. Wilson found a home in Detroit, which had a larger population of middle-class blacks. Ironically, his best season in the majors was 1967. With a 22-11 record, he led the Tigers to within one game of the American League pennant. The winners that year? The Impossible Dream team of his former mates.

He had the opportunity to pitch in the World Series the next year, however, as the Tigers won a championship, something the Sox did not accomplish until October.

He was purchased by the San Diego Padres in 1970, but Mr. Wilson pitched only briefly in the National League before retiring.

In his 11-year career, Mr. Wilson won 121 games and lost 109. Besides being a fierce pitcher, he was one of the best-hitting pitchers. In the era before the designated hitter, he hit 35 home runs -- two shy of the Major League record by a pitcher, held by Wes Ferrell. Twice -- in 1966 and 1968 -- Mr. Wilson hit seven home runs in a season. He also hit some mammoth shots that were among the longest ever hit at Fenway.

He retired and had a successful career in the industrial parts business in metropolitan Detroit. Mr. Wilson, however, didn't leave baseball completely. He served two terms as president of Baseball Assistance Team, which helps out indigent retired ballplayers and umpires whose careers ended before pensions were granted.

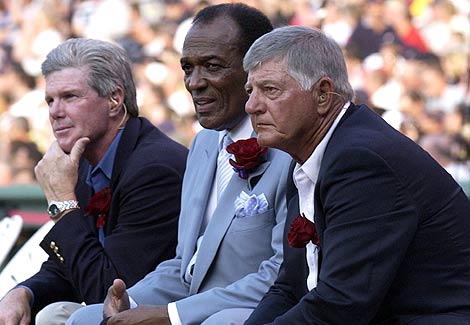

''He was a great kid from the day I met him," Johnny Pesky, the Sox legend and one of Mr. Wilson's former managers, said last night, ''always, always a gentleman."

A moment of silence was held in Mr. Wilson's memory before

yesterday's game at

Mr. Wilson leaves his wife, Roslin; three sons; five grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

Funeral arrangements are incomplete.

Material from the Associated Press was

used in this obituary. ![]()

Earl Wilson with Red Sox catcher Bob Tillman in their dressing room June 26, 1962 after Wilson pitched a no hitter against the Los Angeles Angels at Fenway Park in Boston. Wilson also hit a home run in the 3rd inning to win the game 2-0.